The Upstream Series is an essay series where Dean Reed engages with the leading practitioners within the AECO community. The goal of the upstream series is to improve how design and construction projects are delivered by asking the question "what should be done upstream to make design and construction better?". In this series, each person will share a few ideas that the industry should adopt and use to make projects faster, safer, and better value for the money.

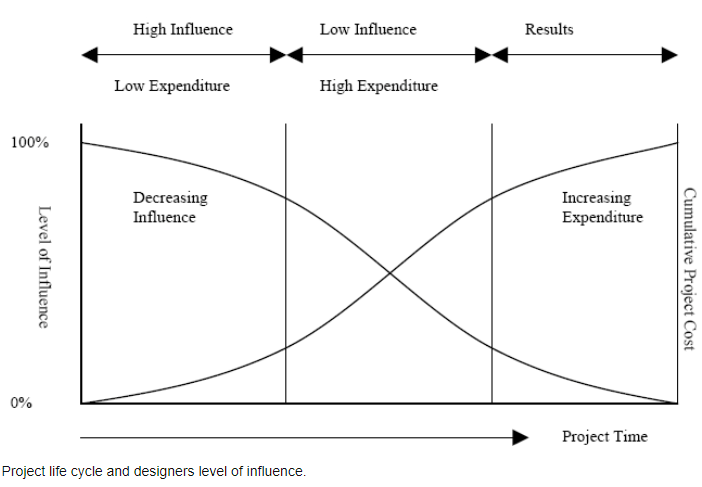

How do we know whether a project is on track or not? During the construction phase, this question can be answered relatively unambiguously, but in the design phase, the answer is often less clear. This article argues that the answer matters enormously, because the design phase offers the greatest opportunities for influencing and optimizing project outcomes.

Traditionally, there are two measures to gauge if a project is on track: costs and deadlines. In the case of costs, we can compare the current costs with the budgeted costs. If these are lower than budgeted, the project is on track. If they are higher, something is wrong. This comparison requires an examination of the costs in sufficient detail and a database of reliable, comparable benchmark costs.

The same methodology applies to the second metric, deadlines. Costs are better suited as a parameter for project control in the design and submittal phases, while deadlines are better suited for the construction phase. (Unit costs can be compared between projects, while schedules are notoriously unreliable during the design phase). If deviations from the benchmark costs are detected, there obviously is a problem. This means that costs are retrospective in nature and are therefore more suitable for controlling purposes and less suitable for proactive project management.

What we need are more suitable metrics for forward-looking project management metrics in the design phase. Furthermore, these metrics should be easy to measure on an ongoing basis. These measures should verify that the design has been optimized in terms of constructability, sustainability and ensure that the design meets the client requirements.

The approach described here is based on the work we have done for our clients using our AppEx knowledge management software tool and a process model that we developed for the design and procurement phases of a project. In our experience, success is based on the combination of this tool to track if the client is getting what he wants, and a process board as a strategic scheduling method that tells you if you are on track. Here is how it works.

The first measure is to track if the client is getting what he wants. This only works if the Owner provided a clear definition of his needs at the outset: what are the project goals and how are they tracked? Which deliverables will be created by whom? With our software we track the qualitative and quantitative requirements that these deliverables have to meet so sound decisions can be made. (These requirements are also known as design acceptance criteria). All these questions can be answered conclusively on an ongoing basis, as proposed above.

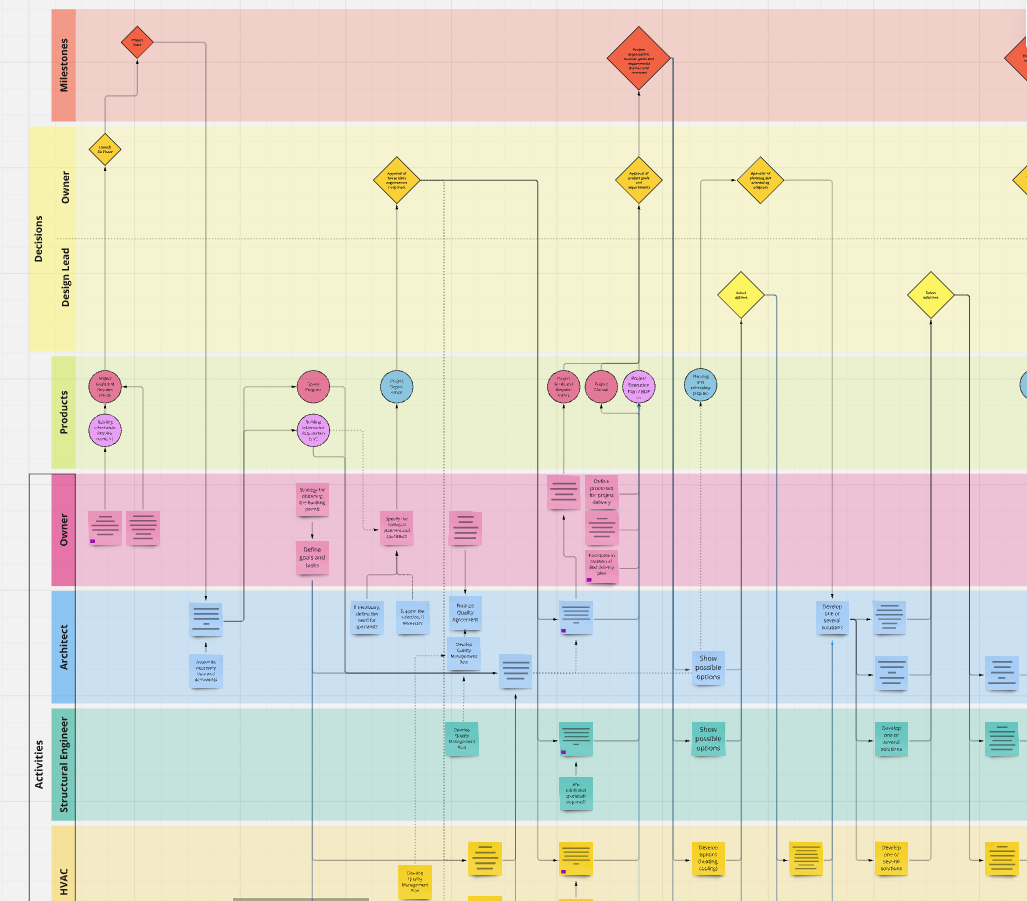

Secondly, we use a process board, similar to the ones commonly used for lean construction. This board is based on a process model that defines the milestones, the decisions by the Owner and the required products or documents in order to make these decisions. We work backwards from the milestones:

- What decisions need to be made in order to meet the milestones?

- What deliverables need to be provided in order to make these decisions? These deliverables need to meet our defined design acceptance criteria (see previous paragraph).

- What are the coordination activities that need to take place between the different design trades in order to ensure that the design is coordinated and buildable?

Together with the necessary activities and dependencies, this process model functions like a strategic schedule.

Above: sectional overview of the process board showing the milestones as red chevrons, decisions as yellow chevrons, and deliverables as circles. The swim lanes show the design team activities and their dependencies, sequential or reciprocal. These activities and dependencies are required in order to ensure a coordinated, buildable design.

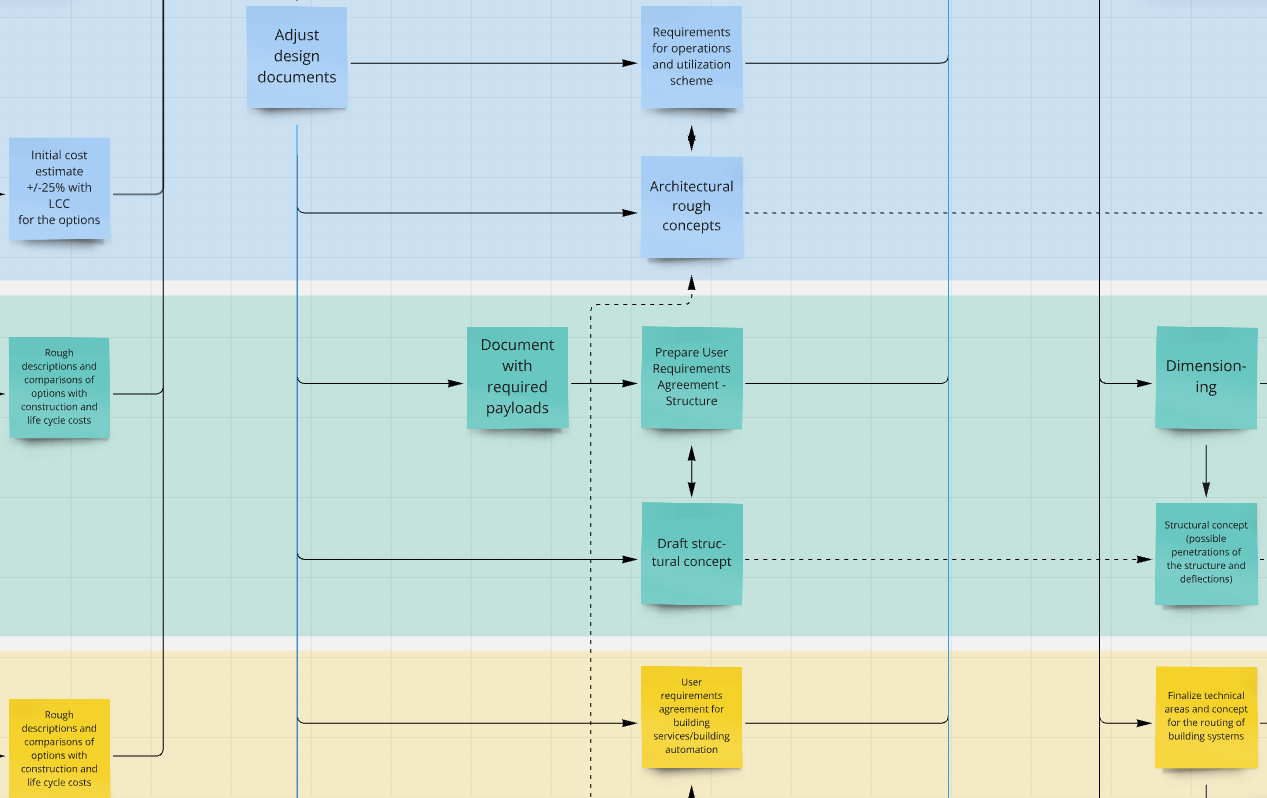

Detail of the process board, showing the early stages of the design development phase.

This process board or strategic schedule differs from a conventional schedule because it relies on a logic of required dependencies that is not as obvious in the design phase as it is in the construction phase. On the jobsite, the sequence of construction is usually predetermined by structural or spatial dependencies. For instance, you can't install doors before the walls are built. These kind of dependencies aren't that obvious in the design phase, but they exist and the project team needs a common agreement about these dependencies in order to proceed efficiently.

Note also that the sequential logic of a process board allows us apply the same lean scheduling methods to the design phase that we have become accustomed to use in the construction phase (e.g., Last Planner).

By tracking these two measures we are able to ensure that our projects are on track and track that the design meets the needs of the owner.

We are currently using this methodology with owners, GC's, architects and design firms in Switzerland. You can contact me at chris@appex.ch or visit https://appex.ch to learn more.