In the early 2010s, Aleksi Heinonen learned how to renovate all 1,500 hotel rooms on a cruise ship in two weeks. He thought that Porsche's lessons in takt production applied to the project could be of interest to builders. Googling helped find the numbers of a couple enthusiastic lean builders, and after a couple of phone calls, there was no going back to the old way of building and waiting.

It looks something like this…

Aleksi Heinonen, Msc. in Industrial Engineering, didn't know any builders, so he googled to see which builders might be interested in how 126 hotel rooms are renovated in a day using Porsche's takt production recipe. Photo by Seppo Mölsä.

In construction, loose schedules have been encouraged by the fact that contractors are frontloaded with payments. The pressure to shorten schedules has therefore often come from the clients.

"Now that interest rates are rising, the pressure to shorten lead times will continue to grow, as owners want their money quickly returned," says Heinonen.

Working for Nokia in the early 2000s, he saw that you have to learn to love speed and hate slowness, as the new factories had to get mobile phones to market quickly. In the car industry, Toyota, Porsche and BMW had already started to use lean to speed up their lead times and demanded the same from their construction projects.

Cruise ship owner Royal Caribbean was also in a hurry, with downtime on the dry dock costing 1 million to 2 million USD a day. It decided that it should be able to carry out cabin refurbishments as part of a mandatory engine overhaul lasting a few weeks also for the biggest ships of their fleet. The method chosen was takt production, which had been tried and tested in a German shipyard. The management of I.S. Mäkinen Oy, the company chosen to carry out the cabin refits, was taken to Germany to see the takt production system designed by Porsche Consulting for the Meyer shipyard. Aleksi Heinonen, Msc. in Industrial Engineering, was hired in 2012 to assist Mäkinen in the implementation of the takt production for the cabin refits.

The results were astonishing: lead times plummeted and quality improved. From a baseline of 35 cabins per day, the takt production process immediately enabled the renovation of 62 cabins per day. In two and a half years, the operation improved so much that the sixth project reached a daily rate of 126 cabins and 1500 cabins were refurbished in two weeks. Whereas before, hundreds of defects were found in the cabins after the renovation work, which were corrected during the next cruise, in the takt production, defects were corrected within an hour of the completion of the renovation of each cabin, and the defects in the first cabin were not allowed to be repeated in the next.

An American TV company visited the Bahamas to marvel at the speed with which the Finns were renovating the ship's cabins: 1500 cabins in a few weeks. In 2015, the builders invited Aleksi Heinonen to their lean seminar to show them how it's done.

Contact builders by Googling

In 2015, Heinonen suggested that there could be huge potential for takt production in construction. As he didn't already know any builders, he looked up the contact details of Lean Construction Finland online and called its leader, Vison founder Lauri Merikallio. The latter advised Heinonen to contact Juha Salminen, then Development Director at Consti. Salminen was familiar with Porsche's takt production model and the theory of takt production, but in Consti's own experiment, in the renovation of the Scandic Continental in Helsinki, the interior designer had confused the takt with his constant changes.

The theory was put into practice when Heinonen showed how to meticulously break down the work stages in the area and how to manage the activities with discipline on site. The balcony renovation in the Jyrkkälä suburb of Turku was chosen as a common test site. Heinonen coached the site staff in how to plan a takt schedule so well that, even though the renovation did not ultimately go ahead, Consti was able to apply these lessons successfully to the subsequent plinth renovation.

Salminen invited Heinonen to LCI Days in 2015 and to a RAIN seminar in 2016 to demonstrate to builders how to repair ships using a minute-by-minute schedule. One of the enthusiasts was Henri Jyrkkäranta, Director of Construction Services at the University of Helsinki, who proposed the renovation of Yliopistonkatu 4, or Tiedekulma, as a pilot for takt production. SRV, the general contractor, had the courage to experiment with takt production, even though it was implemented after work had already started. Heinonen says that the takt schedule visualisation he used on this project has since become almost the industry standard.

The renovation of the University of Helsinki's Tiedekulma was the first time that Aleksi Heinonen had designed a construction project using takt-time. The presentation technique used there is now well established.

Heinonen also called to Olli Seppänen when he discovered that he had been appointed professor of Operations Management in Construction at Aalto University. Although Seppänen was the founder of a scheduling software company, his first reaction was that takt scheduling could not work because it did not have enough buffers. A line-of-balance schedule leaves up to a couple of weeks of buffer between tasks.

When Seppänen saw the results of the cabin refurbishment, he became so enthusiastic about the idea that, together with Heinonen, he wrote a paper on Takt Time Planning: Lessons for Construction Industry from a Cruise Ship Cabin Refurbishment Case Study for a IGLC seminar in Boston 2016.

Seppänen, who had worked in America, brought back a model for an independent entity within the university, Vision 2030, now known as Building 2030. Takt production was one of the first things that the twenty companies that signed up to participate went to learn about. The pilot sites used both German and American implementation models.

The speed of the breakthrough was a surprise

The breakthrough in takt production is reflected in the fact that by 2021, it was already being used in more than 200 projects. Heinonen has been involved in 50 projects through Vison. So a few phone calls have started a cultural revolution in construction. According to Juha Salminen, the best way to make it a reality is for master craftsmen who have acquired a taste for takt production to develop it on their own at their next construction sites.

The growing popularity of takt production has surprised even lean experts. In 2019, Jan Elfving, Skanska's head of development, still estimated that the breakthrough would take years. Now he happily admits he was wrong. "In the interior construction and handover phases of homes and offices, takt production is becoming the rule rather than the exception at Skanska."

In 2003, Jan Elfving wrote his thesis on the use of lean in construction at Berkeley, California. Disney was one of the first to get excited about the subject and offered a pilot site. Lean's popularity exploded within five years.

Juha Salminen, author of "Lean in Construction", acknowledges Aleksi Heinonen's pioneering work and energy as a promoter of takt production. Olli Seppänen also played a major role in getting a large number of companies to try out takt production. In Salminen's view, successful development in the construction sector often depends on the will and perseverance of a few people.

"Sometimes the critical threshold is crossed, sometimes not. Sometimes it takes several attempts before a breakthrough happens."

A sad example of that last is lean construction itself. Lauri Koskela wrote the first, internationally widely circulated article on it back in 1992. In Finland, however, 'lean construction' did not attract the interest of builders during the recession years of the 1990s. It was only in the 2010s, with the advent of alliance contracts, that lean made a new appearance. At the same time, lean tools such as big room and last planner became more widespread, making them familiar to builders when takt production started.

Takt production is best suited for interior works

Already in 2018, takt production was found to be well suited to repetitive spaces, such as the interiors of housing developments and home renovations. In 2020, it became established in office construction and in 2022 it was also found to be suitable for the overall scheduling of megaprojects.

Elfving cites the Ilves Hotel in Tampere as a prime example of a renovation project. In this case, takt production was tried out with a small risk, but the results exceeded expectations. At Consti, a similar experience of success came in the case of the Holiday Inn at the airport. NCC, on the other hand, practiced takt production in a hotel project in the Pasila Konepaja area.

The Atlas and Hyperion skyscrapers under construction in Helsinki are the latest example of the benefits of takt production. The German client Union Investment set such a tight schedule for the project that Skanska had to plan the frame and interior works to closely follow each other in order to meet the demand. One storey will be erected in eight days and the same will be achieved for the interior work. This model is likely to be used for the skyscrapers going up in Pasila.

The tower house is ideal for interior work on a timetable, because there is a huge amount of repetition, there are hardly any workable backlog and there is only one direction to go. There will also be no change from the tenants in the Vuosaari rental housing project.

In Skanska's first version of the timetable, the skyscraper floor was divided into two four-day periods, but this was abandoned and the interior work on the entire floor will be completed in eight days. In addition, the schedule was divided into three sections, namely dry areas, wet areas and the corridor. However, this division and the timetable on the office wall only serve the big picture. The actual scheduling work is done in the traditional way, apartment by apartment.

"For a residential project, a floor division or a division into dry and wet areas is far too inefficient," says Teemu Kouri, the site manager.

"At the level of floor-by-floor scheduling, you can prepare for disruptions, but the activity planning itself has to be done at a much more detailed level," says Markus Ylinen, a scheduling engineer specialising in takt planning. In practice, each team has a half-day window on each floor to complete the work.

So there is not just one target time for the completion of a floor, within which the work can be freely done, but within which there are many milestones. These are achieved through good forward planning, rigorous monitoring and rapid corrective action.

Completing once and for all improves quality

Lead times for interior work have been reduced by an average of ten percent on Skanska's takt production projects, and in many cases even more, but Elfving believes that more importantly, takt production clearly increases quality.

"Takt production forces you to finish in small units at once. Then you have to think about quality more than usual and check it much more often to prevent errors from recurring."

Skanska regularly measures whether the conditions for starting work have been right and how successful the self-assignments have been. This data, says Elfving, clearly shows that the old belief that tightening the schedule would reduce quality is not true.

"The takt schedule does not mean that disruption will be eliminated, but it will reduce disruption. The less disruption on site, the more cost-effective and consistent the work will be. And when the schedule is trouble-free, the cost forecasts are clear," says Kouri.

Heinonen says the best way to increase productivity is not to rush workers, but to create the conditions for smooth work and remove obstacles. In the case takt production, the fact that the subcontractor who is continuing work is not just arriving on site but working in the next room makes things run more smoothly. For example, on a Const repair site, a plumber was able to tell a diamond driller where he thought the holes for the drains should be drilled. This took away one big pain point.

"People behave differently when you take out unnecessary buffers. Then the urgency is understood better. The next trade won't get to work if we don't get it done," says Heinonen.

According to Heinonen, takt production emphasises the importance of ensuring the conditions for work by limiting the degree of freedom in production to correct defects made in earlier stages. In Juha Salminen's view, the takt production has brought good work planning back into the construction industry.

Tiler Märt Hödsi waterproofed the bathroom of the Bonus Inn hotel in March 2020. Takt production also makes it easier to monitor the quality of waterproofing work. Photo by Jussi Helttunen

A small batch size quickly reveals mistakes. In a hotel project with an takt production system, the first hotel rooms are completed a few months after the start of the project, not six months later. If the client is not satisfied with the quality, he can have repairs made in the first rooms. Correcting the workmanship will then prevent the errors from recurring.

The most worrying thing, according to Heinonen, is when small daily mistakes go unnoticed or are kept quiet. In his view, the idea that things go wrong is a kind of part of takt production.

"If we don't accept that we live with small deviations and learn from them constantly, competitiveness will not develop."

Sub-contracts need to be both supervised and managed

This kind of mindset requires a new kind of leadership on the job site, which Joonas Lehtovaara, who developed takt production at Fira, recently wrote a dissertation on.

"The culture change in construction in the near future will emphasize the self-direction of teams and individuals. This, combined with more effective transparency and knowledge management, offers the opportunity for a productivity bonanza," Lehtovaara reflected.

According to Heinonen, the complementary nature of individual responsibility and collaborative problem solving are key to agile and psychologically safe leadership.

Work safety has been improved on construction sites by getting workers to openly report any shortcomings they have noticed. However, Heinonen says that the same decentralized control has not yet been put in place for quality control, as foreigners in particular do not want to maltreat their countrymen. That is why Heinonen himself carried out very detailed quality checks on the cabin refurbishments, starting with putty seams and grimy carpet edges, before the next crew was allowed to continue. However, the feedback and support given to the workers soon led to zero defects.

On construction sites, foremen have been replaced by supervisors, who take over a subcontractor's work before the next one can move on. However, Heinonen believes that the role of foreman should not be blurred. Mäkinen's cabin renovations were carried out by foreign partners, but Mäkinen used much stronger directives than is common on construction sites today.

"Our partners were so well integrated that they practically operated as one company," says Heinonen.

The reliability of subcontractors is critical to the success of the takt production, because the takt is confused by a single non-performing contractor. Skanska therefore uses an exceptionally high number of its own employees and familiar subcontractors in its housing production, with whom it has been possible to agree that defects will be rectified within the timetable. Although the workers are familiarized with the quality requirements through model work, Kouri says that these must be clarified for the contractors from time to time.

"There is also a certain amount of turnover in the workforce, so contract supervisors have to be vigilant to ensure that quality is maintained. "

Subcontractors excited after initial doubts

Many takt production sites have already reached the four-hour pace, a very small batch size. In Germany and the US, on the other hand, the takt-time of a week is still considered to be the most sensible batch. The upside is that traditional resource balancing methods do not need to be changed when subcontractors move to another site after completing that week's work. The risk, according to Heinonen, is that subcontractors will jump from one site to another randomly.

It has not always been easy for subcontractors to adapt to the new production schedule. In the first pilots, some subcontractors even refused to take part, when the project was brought in in the middle of the process, after the subcontracts had already been signed.

Jan Elfving says that in Skanska's first takt production projects, the challenge was to get subcontractors to trust the general contractor's schedule promises. Reducing their own buffers requires trust in both the general contractor's schedule and the other subcontractors.

If one link in the chain fails, for example because of illness, the whole chain fails. That is why there must also be workable backlog on site to balance the resources required to keep up the pace. Another option is to have a designated replacement for the workers or a site where they can be sure to be called on the same day.

Kouri says that the most important and most difficult thing on the Vuosaari site was to get the subcontractors to understand the concept of takt production. They also had to understand that there are jobs on the floor that can be completed by one guy in such a short time that he can visit many other sites. The screeding and painting work, on the other hand, has long drying times that have to be taken into account in the schedule.

According to Heinonen, subcontractors and their employees need to be familiarized with the process well in advance. Commitment is best achieved when everyone has a chance to express their views on the content and schedule of the wagons, and in the morning meetings, obstacles and deviations are openly brought up and solutions are sought together.

"The takt production schedule forced interaction, as the general contractor does not know how much time the specialized trades will take to complete their work or what the optimal sequence is for them. That's why it was good to involve them in the planning of the schedule," says Elfving.

If subcontractors were skeptical and even fearful in the first takt pilots, today subcontractors are already asking Heinonen which construction companies take takt production most seriously, i.e. which ones are worth working with. Like Amplit, which has been in the business for a long time, subcontractors have found that everyone, from the installers onwards, wins when the work goes more smoothly than in the traditional way.

Mega-projects have mega-sized digital challenges

The most ambitious development work is done on demanding megaprojects. According to Heinonen, it is especially important that the decision on the intent is made at the beginning of the project, so that it guides the activities. A good example is the extension of the T2 reception hall at Helsinki-Vantaa Airport, which Rakennuslehti has chosen as its site of the year 2021. SRV's complex mega-project was several months under budget and under schedule.

"This is a big hero story to tell well beyond Berlin," says Heinonen, who was involved in the project. "Using one-day-takt-time in a non-repetitive space, with phase schedule optimisation despite the challenging environment."

However, T2's takt production was not without its problems. According to Ossi Inkilä, SRV's unit manager, the challenge was waking up too late to streamline the design and plan the supply chain to the takt. "On the other hand, the covid hit at the worst time, when the daily management practices should have been up and running."

The same T2 alliance partners are committed to moving takt production forward at Laakso Hospital in Helsinki. Its alliance is not just about setting the takt for individual work phases, but about bringing the whole project – hospital operative planning, design, procurement, construction and commissioning – into the same flow.

For T2's project manager Ossi Inkilä, takt production was a challenge of continuous improvement.

Skanska has partly mixed experiences with the use of takt production in the extension of the University Hospital of Oulu. It has been a challenge to manage a complex project. In Elfving's opinion, the management of the huge amount of data in the giant project could have been facilitated by a digital tool. Updating tens of thousands of takt production cells and informing of changes is a huge job when done manually, because when one cell moves, so do all the others.

However, the takt production application developed by Skanska and Flow Technologies (Fira) was not ready when the Oulu project started. Such an application is most useful for documentation. When everyone logs the progress of their work into the system, the progress of the site is visible to everyone in real time. The Ahvenisto Assi hospital site already has this tool for takt production and has been able to transfer best practices from the Oulu hospital site.

Heinonen says the problem with digital tools has been that there has not been enough computing power to run even the one-day-takt schedules of conventional projects, let alone mega-projects. Even a small pipe repair site has a few thousand cells on a timetable. A couple of years ago, according to Heinonen, the situation was such that only one of the four tested takt production software could run it. On a large hospital site with a one-day-takt schedule, there can be 50 000 cells. When you add in the local submissions and the system has to be redesigned and rebalanced at least weekly, the calculation and redesign becomes so complex that the tested software’s were not powerful enough, according to Heinonen.

Digital tools have been developed specifically to provide situational awareness. However, Heinonen believes that there is less need for it on a well running takt production site. On a traditional job site, situational awareness is often very poor, but when you get the process up to speed and start building with a small batch flow and transparent buffers and daily management, situational awareness is on totally another level.

Heinonen noticed this already during the cabin renovations.

"The consultants had suggested using cabin door checklists to monitor the progress of the work. In practice, they turned out to be useless, because after the second project, the process was never again so broken that the foreman needed a checklist to get situational awareness."

Heinonen believes that digital tools are particularly needed to support planning and replanning. The integration of quality management data into the schedule would also require development.

"However, these have not been developed, and the investment has been spent on enabling management to check the situation on the site from their mobile phones without having to visit the site," Heinonen says, only slightly more pointedly.

For the superintendent, it has always been a matter of course to go to the site to see what is being done and talk to the workers. It's done without having to talk in lean-terms about a gemba walk.

According to Heinonen, no software should try to eliminate quality control and face-to-face discussions. Skanska's Vuosaari site is well aware of this. The site was up and running before the takt production application was ready, but it was still not felt necessary. The project is so repetitive and things are so manageable on one floor that the information provided by the contractor meetings is sufficient for the site management to get an overview of the situation.

"We don't want the software to just click 'activity complete' and move on to the next job. Skanska's site management has to see it for themselves, because Skanska has the overall responsibility for quality towards the client," says Project Manager Mikko Borg.

HOAS has a similar experience from an owner's perspective. According to Laura Pääkkönen, the construction manager, you cannot manage takt production site from the site office, daily management must take place on site in continuous active interaction with the contractors. Rapid reaction to observations and feedback, and quick access to the client and planners are key.

"It has also been seen as important that the tradesmen themselves, and not just the bosses, are also rewarded for success in takt production," she says.

Preparing for hidden surprises on the infrastructure side

Skanska has successfully tried takt production at a railway construction site in Helsinki, where more than 20 takt areas were used. However, the infrastructure side is lagging behind building construction in the field of takt production. This is partly due to the fact that in infrastructure construction, it is difficult to achieve uniform duration of work phases due to the unpredictability of the underground conditions. A highly publicized project launched by Mayor Jan Vapaavuori to streamline street works in Helsinki proved disappointing, as new surprises kept popping up underneath the old street network. For example, when an excavator broke a sewer or water pipe that was more than a hundred years old, the whole site came to a standstill.

But lessons have been learned and, for example, the Kalasatama to Pasila project is doing great things, according to Heinonen. The project is being built by two alliances, one involving Destia and the other GRK.

For an infrastructure project, the Kalasatamasta Pasilaan project makes exceptionally good use of takt production. Photo Destia.

Design managers Riikka Sihvola and Petri Korkiakoski from Destia say that one of the key objectives of the KaPa Sörkan Spora alliance has been to reduce lot size, which has been pursued in all blocks. The construction conditions underground and in the surroundings of the blocks influence how clear the path of construction for the takt train and wagons can be achieved. For example, on Hermannin Rantatie, the construction sequence of the pipeline and line crossings and the traffic arrangements during the work have formed a critical path for the construction, according to which the construction of the piling slabs has been staged and divided into smaller more manageable areas (named slabs and channels) in which these wagons will proceed.

In the master schedule made during the alliance development phase, the line was divided into takt-areas of approximately 126 m based on the logical progression of rail installations per week, and the takt production was planned to be used for such activities as embankment and piling construction and track superstructure works. This was the basis for the subsequent takt planning, which moved to a one-day-takt-time, and the principles of takt planning have been applied to entire street areas and blocks, covering all types of work (earthworks, base reinforcement, concrete roadworks, municipal engineering, infill, surfacing). For example, the takt areas for the one-day-takt-time "Aallonhalkojakatu" are currently typically 36 metres.

When determining the wagon workloads, the aim has been to achieve the smoothest possible workloads. Fully uniform contents have not yet been achieved, but for example, the superstructure of the tramway on the Aallonhalkoja is being built at daily rates.

The project has identified the lost concept of “making do”, coined by Lauri Koskela. It means working, even though the conditions for the work do not exist or have ceased to exist due to disruptions. Typically, several teams may be working at a takt-area, with workers, materials and tools getting in the way of the work. The takt-area must therefore either be reserved for one contractor at a time or the work must be planned so that it can be carried out without disruption in the same area.

Sihvola and Korkiakoski say that the trades have been pleased to have a clear view in advance of where and when their team will work. However, takt production requires more detailed planning than normal, ensuring that the conditions for the work are right and that the designers are present on site so that problems can be solved quickly together. The challenge is to get used to flow efficiency rather than resource efficiency and to get used to collaborative meeting practices. For subcontractors, this requires a long-term commitment.

The term "takt production" is used loosely

So, while builders are becoming familiar with the term 'takt production', in many projects its content is still quite varied. According to Juha Salminen, a large part of takt schedules are in practice line-of-balance schedules using Excel as a presentation method. In orthodox takt production, the work activities are planned in packages of equal workload, "wagons", and these are run consecutively in an agreed time frame. Production can be divided into wagons of equal workload, even if they are not identical in terms of work content.

A decision to implement takt production must be taken early on, as many design decisions are made at the initial stage which are difficult to influence later on. In practice, however, it may have been decided in the middle of construction to make up for a delay in the schedule. In such cases, the conditions for takt production are obviously not very good.

"Whenever design and construction are overlapping, the flow of owner requirements, design and procurement to the construction site pull is of paramount importance. It's exciting that the construction industry seems to have woken up to the fact that plans should be ready before you build, only after you've introduced the use of takt production," says Heinonen.

In 2019, when he analyzed the takt production projects of the time, it turned out to be a much more flexible method than the site management had feared. The most doubtful aspect was getting the design pulled to takt. Interestingly, contractors and designers had widely diverging views on whether designs had been delivered on time. In the Building 2030 survey, designers claimed to be well on time, while contractors' comments were quite the opposite.

Heinonen believes that takted construction and takted design are a better match than non-takted construction and non-takted design.

At the start of a project, takt production requires more work planning, procurement planning and material flow management than traditional construction, but if this initial planning phase and the subsequent re-planning phases that are integral parts of takt production, are well managed, the rush towards the end of the project is avoided. In that "final war", Olli Seppänen says, the schedule is often forced to be met without regard for money, quality and well being.

Lead times have not yet decreased

An interesting question is how takt production and Integrated Project Deliveries have affected productivity development in construction. In individual projects, takt production has led to improvements in lead times of tens of percent, but has this had an impact on the average lead time of a construction company?

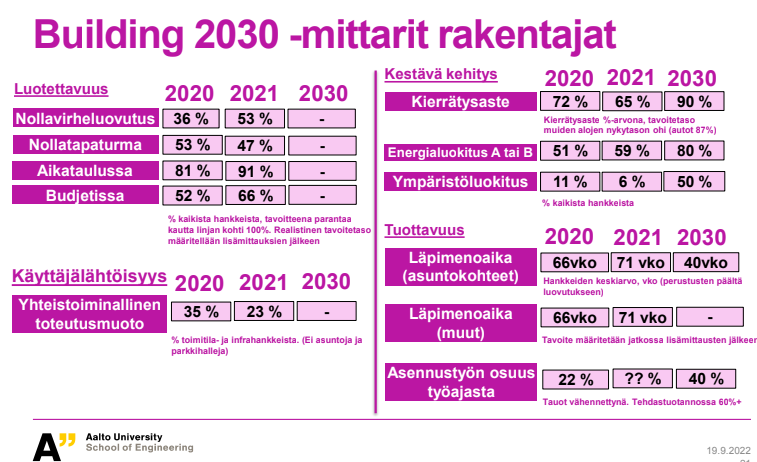

The Building 2030 consortium developed measurement criteria to assess the progress of construction sites in 2020 and 2021, to be measured annually. Already the first measurement showed that the reliability of the companies' performance, such as on-time delivery and flawlessness of deliveries, has improved. As many as 91% of the sites were on time, which according to Mr Seppänen is a top result internationally, as the average in many countries is only around 50%.

"Perhaps it also reflects the slackness of our schedules," he said when reporting the results last autumn.

Builders are still far from the Building 2030 target lead time, but the reliability of their work has already improved.

Takt production was not yet reflected in the average project lead times. They had even increased, although Seppänen said this was explained by the fact that there were significantly more projects in the second round. In house building, the lead time has stagnated at around 70 weeks, with the aim of reducing it to 40 weeks by the end of the decade. The time has been calculated from the top of the foundations to handover.

The challenge for the sector is to replicate the successes of takt production in basic production and how to improve performance in unique places such as schools and kindergartens. These were the most problematic by all measures. These have often been addressed through collaborative approaches.

On the housing side, the lessons learned from CC have been easiest to transfer from one site to another. On the office side, this has been more difficult. In particular, the importance of the up-front planning required by takt production may be underestimated, according to Elfving. The shortcomings then multiply when each stage of the takt process has to be completed at the same time.

Skanska has the advantage of having its own scheduling team, which provides training support and spars projects already at the tender stage. In Elfving's view, the transfer of lessons learned is therefore less of a challenge than the low level of ambition, which is explained by the fear of failure.

"We should dare to be even more ambitious in terms of timelines."

Elfving sees two further challenges in developing the concept. The first is the need to pull the detail design to the takt production. The second is material logistics. There is a lot of work to be done there.

"Takt production implies using staged material deliveries, so you only import the amount of material that you can install in that takt-area at a time."

Good logistics is paramount for the functioning of takt production. At Hyperion, all the materials needed for a room are brought in on time.

In some respects, Skanska was already ahead of the curve in material logistics in 2006, when the Reimantorni was being built in Espoo. There, it was possible to digitally track the flow of every single concrete element and window in the construction chain to the site. However, the system developed with Nokia at the time was left unused. The technology at the time could not be scaled up at low cost, but now it could be.

Takt production to drive the business

Heinonen points out that, despite the good results of individual sites, takt production is still in its infancy.

"The takt has very much been the takt of the site. Compared to what was done in the cruise ship cabins or what it could be on the way to a more industrial and productive, higher quality, safer and more pleasant working environment, only small things have been done on the site, and even there mostly in the interior work phase."

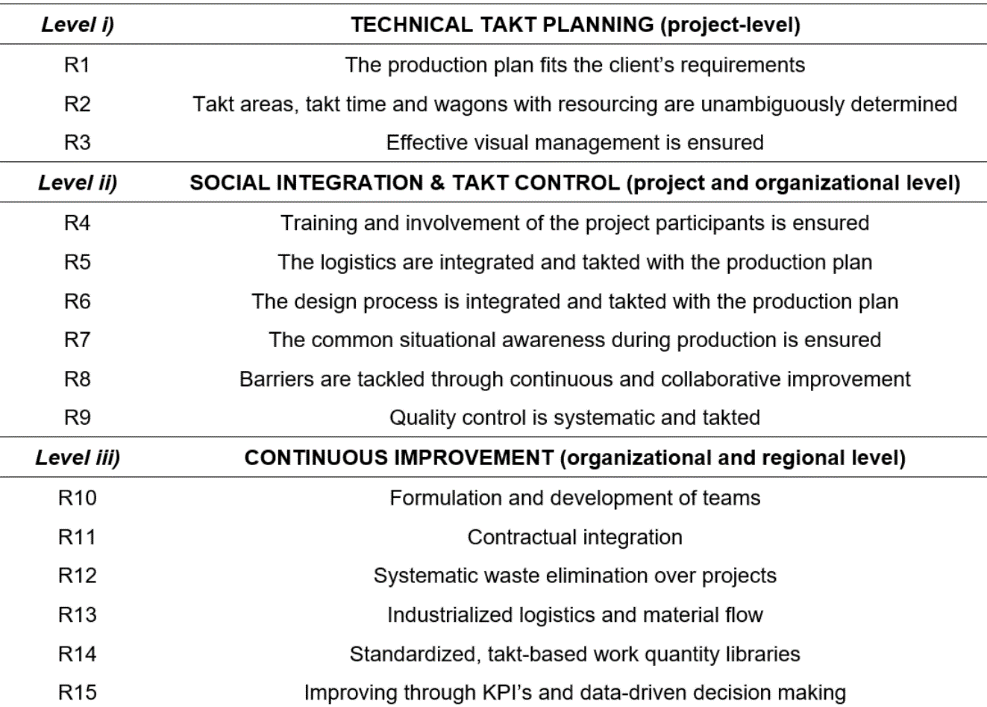

The first steps are being taken to develop the maturity of contract manufacturing. Building 2030 aims to get all projects to level 1 and a growing proportion to levels 2 and 3.

According to Mr Heinonen, takt production could form the basis for the company's entire production strategy. This could take the form of smarter prefabrication and design solutions to support production.

Already at the 2015 LCI seminar, Heinonen instructed builders that flow efficiency and takt production should be thought of as a strategy. "If the client had thought about ship refurbishments in terms of cost savings, the application of lean would have been limited to one or two ships. In the early stages, speeding up lead-times required additional resources, but in later refurbishments, the use of resources also decreased, even though throughput was dramatically accelerated," he said in a story written by Kaisa Salminen.

Heinonen's vision is that by shortening lead times and sequencing projects to takt, we can move towards flowing mass production, with individual fast trains replacing simultaneous worksites within business units. This will be achieved by entering into long-term partnerships to minimise staff turnover and to ensure continuous human development and operational improvement. This cannot be achieved without addressing the current culture of trying to get the cheapest subcontractors for every project.

A few leading companies are already on this path, where takt production is no longer seen as a single site agenda, but can drive the whole business unit. Heinonen cites the example of Respect Project, which has introduced takt production in all its pipe renovations.

"If owners chose a winning strategy with an open mind and the courage to commit and invest with a professional athlete's grip."

Heinonen believes that the time is ripe for companies specializing in the production of takt to take on overall responsibility for interior work in homes or offices, for example. This would ensure continuous improvement for the business. Heinonen believes that the main obstacle to this model is the middle management of construction companies, whose territory would be encroached upon. They have been responsible for chopping up the works and integrating subcontractors.

Another obstacle to the total responsibility model for takt production is that it is difficult to achieve sufficient continuity. Even for a large construction company with half a billion euros in lots, housing production is not steady. We have seen this very concretely over the last year. Even the cruise ship bani refurbishments have not been able to achieve a steady demand, as covid collapsed the market for several years. This led to the disbanding of experienced cabin refurbishment teams.

The easiest way to achieve continuity is for large property owners such as HOAS and the Asuntosäätiö. They have therefore started to use takt production to sequence their own housing renovation projects. HOAS uses takt production for both heavy basic renovations and lighter facelift renovations. However, works such as waterproofing and common areas and exterior works are carried out separately from takt production. Takts are usually planned separately for wet and dry areas, taking care not to interfere with the performance of others.

Clients with a large real estate portfolio, such as HOAS, are at the forefront of embedding takt production into their business. HOAS has partnered with Renevo. Arto Pussinen and Cristian Munoz-Konnu will delve into the plans together.

According to Laura Pääkkönen, HOAS' construction manager, the takt production has significantly reduced throughput-times for individual apartments and for the whole site, even though the renovations are usually carried out in such a way that it is possible to live there every day. For example, in Viikki Maakaari, Renevo carried out facelift renovations with a lead time of eight days for one apartment. On the two busiest days, six different work activities were carried out in the apartment. If there is a sauna in the apartment, the maximum lead time is ten days. In the five-site basic renovation alliance, the lead time per dwelling ranged from 23 to 35 days.

Comparative data with Norway

Although the takt production was brought to Finland from abroad, mainly from Germany and America, Jan Elfving believes that Finland is already becoming one of the leading countries in the field of takt production and schedule management in general. Elfving is well acquainted with the American level, as he was there in the late 1990s and early 2000s for his doctoral thesis.

"While California has some of the world's top companies that are very advanced in integrated construction projects and takt production, that model is not common in America and in fact in Finland takt production is becoming more routine than it is there," says Elfving.

Based on the experience of the Vuosaari tower blocks, Skanska's Mikko Borg says that the Finns already have lessons to teach their colleagues in other countries in the field of takt production and the vertical logistics it requires.

The Finns came to takt production late, as it has a long tradition in Germany, first in the war industry and then in the car industry. The Norwegians also got into the takt production before us. But Finland has caught up well.

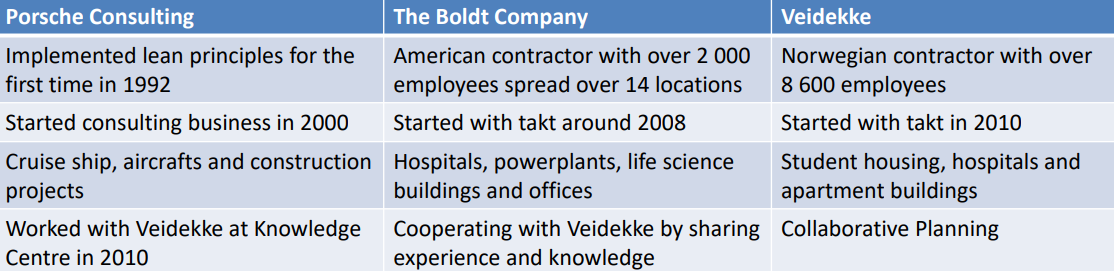

Within the Nordic countries, the exchange of information is most active. The Swedes are interested in the excellent scheduling skills of the Finns. The Swedes are not familiar with the line-of-balance chart and do not yet use takt scheduling. In contrast, the Norwegians started learning takt production a little before the Finns, for example Veidekke in 2010 in cooperation with Porsche Consulting.

In 2016, the Norwegians ventured into the use of takt production in a large hospital project. However, the project proved challenging and only a third of the work packages were completed on time. However, they were not discouraged by the setbacks and are now keen to share their experiences with the Finns. Pekka Kujansuu, a specialist in takt production, has spent two years on a Norwegian hospital site exchanging information.

Translated from a article written by Seppo Mölsä and published in Rakennuslehti, June 2023

Aleksi Heinonen

Aleksi Heinonen